Zoning determines the size, shape, style, and location of buildings in a given area. If cities were living organisms, zoning would be their genetic code. As genes determine people’s height and eye color, zoning dictates the land use rules at the local level.

How does zoning work in the City of Los Angeles? Through our local zoning regulations, we are able to transform our broad policy goals into property-specific requirements.

In the City of Los Angeles, we are undergoing a comprehensive revision to our zoning code, in order to craft tailored regulations that meet the diverse needs of our communities.

The current zoning code is the result of decades of amendments and supplemental layers of land use regulations that were added on top of the existing regulations to achieve specific goals that transcended what the prior zoning laws could accomplish. Approximately 66.24% of the lots in the City of Los Angeles have one or more overlays applied to them — a patchwork of regulations that are applied to specific properties across specific geographic areas.

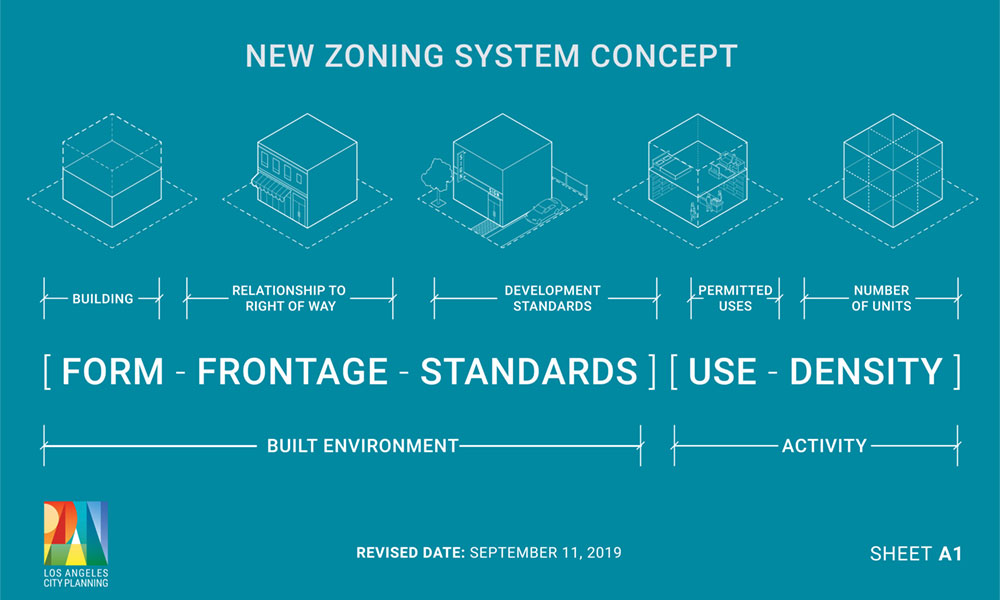

In an effort to minimize the need for these exceptions, City Planning has developed a new and modern framework to regulate the use and form of buildings across the City of Los Angeles. The proposed DNA for our new zoning is comprised of five key components: Form, Frontage, Development Standards, Use, and Density.

While Form, Frontage, and Development Standards cover the built environment, Use and Density refer to the allowable activities on any given site.

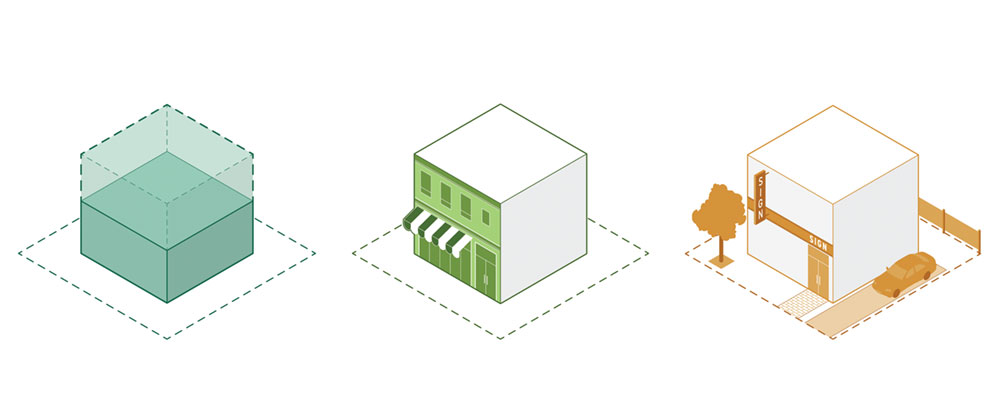

Form Districts determine how big buildings can be. Some Form Districts only allow construction of short buildings, while others permit taller ones. Form Districts are one of the ways a Community Plan can better regulate the scale of buildings along a street or commercial corridor — establishing a cap on the size and shape of buildings.

Frontage Districts determine how the building interfaces with the street. Much of each neighborhood’s special character is created by our experience of a building’s relationship from its streetfront.

Frontage Districts ensure that new developments fit with the feel of the neighborhood — establishing a certain charm by determining building elements, such as stoops, canopies, and patios.

Development Standards are the third part of the zoning string, and cover things like access, parking, landscaping, lighting, and signs.

For instance, Development Standards Districts in Downtown may not require any parking. Other Development Standards Districts may include a range of requirements for a minimum amount of parking that must be provided depending on the proposed uses.

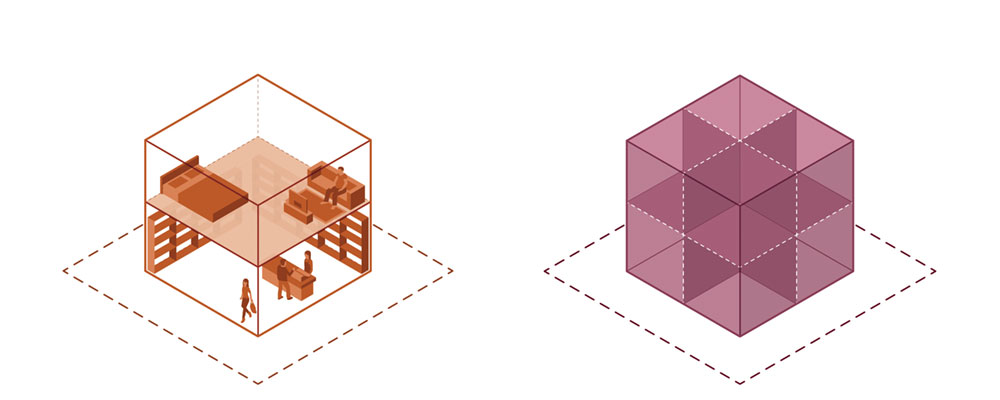

While other parts of the zoning string regulate the built environment, we also need to look at what the building can be used for. Use Districts determine what kinds of activities are allowed on the property.

Each Use District regulates the kinds of uses that are permitted on a property — elaborating on which have limitations, and which ones need special review. For instance, one residential Use District could be designated specifically as a single-family neighborhood, while another residential Use District could also allow some limited, neighborhood-serving businesses (think corner markets).

Another component of the zoning string is devoted to Density Districts. Density refers to the number of residential units allowed on a site. If a site is zoned for greater density, it means more residential units can be built on that site, whereas lower-density zoning means fewer units.

As new Community Plans are developed and adopted, new zoning regulations will be developed. The first Community Plan to implement the new zoning string will be the Downtown Los Angeles Community Plan. To learn more about the Downtown Los Angeles Community Plan and the new zoning string, click here.

By: Jaime Espinoza