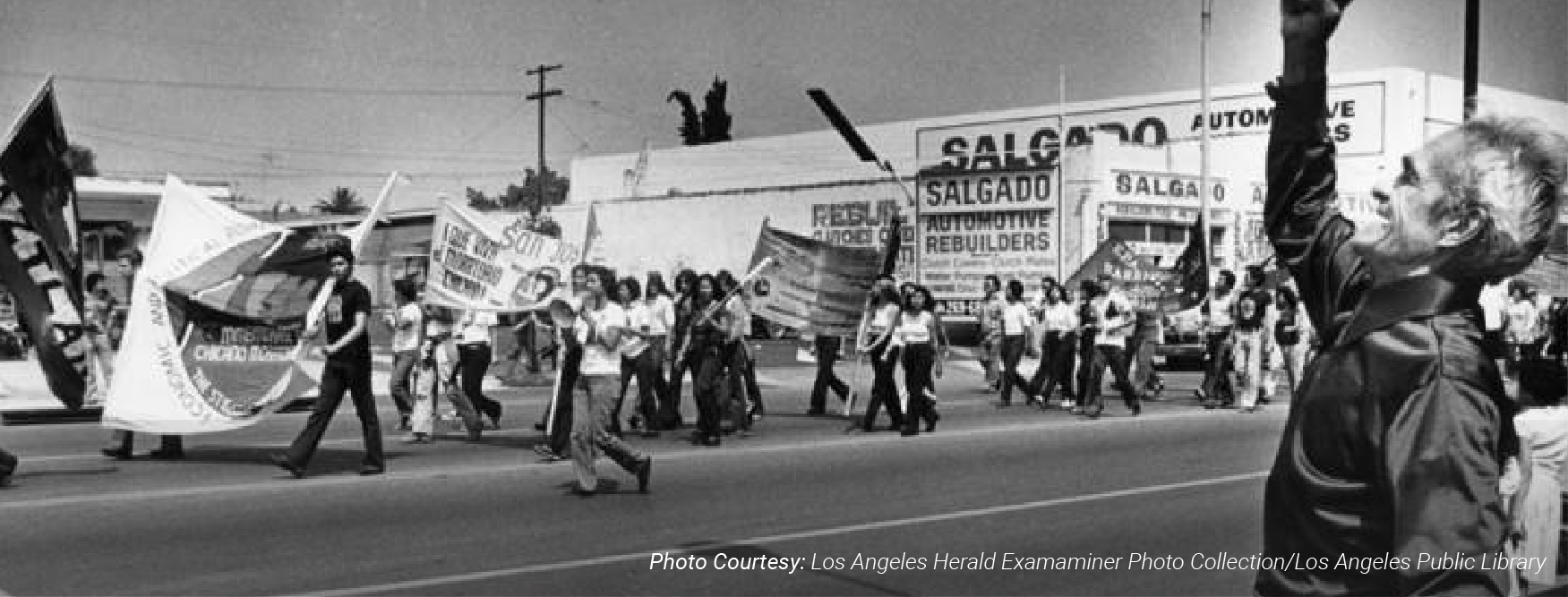

This year has been one of reflection, a time for celebrating the milestones that brought us the freedoms we have today while fighting for an ever-better future for generations to come. It is with respect that we highlight the 50th anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War (Moratorium), the nation’s largest demonstration led by Mexican Americans and Chicanas/os, when 20,000 gathered in East Los Angeles and marched down Whittier Boulevard for justice.

The Moratorium and its immediate effects are widely considered to be the peak of the Chicano movement in Los Angeles, bookending decades of activism within this historic community.

The area popularly known today as “the Eastside,” consisting of the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights and the unincorporated enclaves of East Los Angeles, was preceded by Sonoratown as the center of Mexican American life in Los Angeles. Sonoratown residents were eventually displaced from their neighborhood flanking El Pueblo and moved eastward. Following the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the area flourished with affordable housing and growing job opportunities. Places such as the Boyle Hotel (or Cummings Block, 1899) and Wyvernwood Garden Apartments (1939) became important landmarks for the community, and remain so today. But preserving both the physical and cultural spaces of the Eastside was the result of a decades-long fight.

Starting in 1968, hundreds of largely Chicano youth walked out of Roosevelt, Lincoln, Garfield, and other area high schools in revolt against poor and abusive education conditions, including deteriorating campuses, lack of college prep courses, and racist or indifferent teachers. An estimated 22,000 thousand students walked out, delivered speeches, or fought with police.

At the height of the Vietnam War, Latinos made up only about 10 percent of the U.S. population but about 20 percent of troops killed in combat. In 1970, tensions over the disproportionate number of soldiers of color killed in the war boiled over into a call for a moratorium to end that imbalance.

The Moratorium commenced with people peacefully marching down Whittier Boulevard to what was then called Laguna Park—before the Sheriff’s Department stormed the park and chaos erupted. The violence would lead to three deaths, including that of Los Angeles Times and KMEX journalist Ruben Salazar, whose death was compared by many Latinos to the assassinations of the Kennedy brothers and of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Laguna Park in East Los Angeles would eventually be renamed in honor of Salazar.

At the Moratorium’s 50th anniversary, City Planning honors the courage of the peaceful demonstrators who took part in the events of August 29, 1970. The anniversary is an occasion for the Department to reflect on how historically racist planning practices resulted in redlining, environmental injustice, and heavy-handed policing, and how those issues still play out in Los Angeles and the Eastside today. We take this opportunity to commemorate the efforts and courage of many Chicanas/os during this time who were caught between Mexican-American and identity politics. As Ruben Salazar would say, “Why do I always have to apologize to Americans for Mexicans and to Mexicans for Americans?” Salazar was a key communication bridge between the Chicano community and the rest of Los Angeles, in particular city government.

Similarly, Chicano City Planner Raul Escobedo found himself in the middle when he led the update to the Boyle Heights Community Plan for City Planning in the 1970s. Confronted by a majority-white planning department and a distrustful Boyle Heights community, Raul Escobedo created a participatory and bilingual community outreach process to invite Boyle Heights residents to participate in their plan update process. During this time, residents were concerned about being displaced and fearful of growing development pressures in Downtown Los Angeles and speculation over the industrial river area—two themes that continue to the present day.

As we look to the future of the neighborhood, the Community Plan Update for Boyle Heights is crucial in laying out an equitable planning land use strategy. Compounded by development pressure, the area also continues to face severe environmental injustice, as Boyle Heights is the only neighborhood in the United States gutted by four major freeways. Many of the families displaced by freeway construction and redlining practices were people of color and of low-income. Today, 93 percent of Boyle Heights residents are of Latino, Mexican, Central American, and self-identified Latinx descent; 75 percent are renters; and only 5 percent of the land is dedicated open space. Racial inequities in access to affordable housing options (renting and owning alike), the lack of access to quality jobs, and the scarcity of healthy, recreational open spaces persist. Both City Planning and the community want that to change.

While we cannot erase past practices, we can collectively learn from them and take ethical responsibility to lay a foundation for a hopeful future for all residents in Boyle Heights. Working with and led by local stakeholders, City Planning is currently updating the Boyle Heights Community Plan to provide housing and neighborhood-serving jobs that meet the needs of both current and future residents. Addressing housing during the City’s current homelessness crisis and economic challenges is more important than ever, as Boyle Heights continues to experience some of the most disproportionate impacts of COVID-19. To this end, it is crucial that the Community Plan Update include land use policies from a multi-disciplinary equitable lens. Similar to the efforts of community activists from the 60s and 70s, today’s generation is also working towards equal access to educational and economic opportunities, housing options, open space, health services, and workforce training. The 50th anniversary of the Moratorium is a key moment in Los Angeles history that teaches us that people and organizations can come together and participate in the future of their neighborhoods.

The guiding principles and overarching goals of the Community Plan have been shaped by multiple stakeholders who might have differing opinions, but they all care about Boyle Heights and its sense of place and history. City Planning aims to preserve that sense of place by applying zoning regulations that provide greater access to affordable housing units for Los Angeles residents. In addition to bolstering affordable housing options that minimize displacement, the proposed plan strengthens local business and job growth potential along major corridors such as First Street and Whittier Boulevard. The plan also includes an entire chapter dedicated to the Public Realm and Open Space, and supports the community’s request for a greater urban tree canopy, active recreational spaces, and safe, walkable streets.

For decades, Boyle Heights has maintained its legacy as a community rooted in families. While the majority of residents are renters, these families want to ensure that younger generations not only break that cycle and are able to access homeownership opportunities, but also are able to remain in their neighborhood—one that generations of community organizations have helped to maintain, irrespective of who was or was not in office to represent their voices.

City Planning remains committed to working with various community-based organizations and Neighborhood Council representatives elected by Boyle Heights residents. The Community Plan reflects various voices and opinions on policies that ensure retention of existing housing, cultural and historic resources, small businesses, contextual infill along mixed-use corridors serviced by transit options, and zoning regulations that prioritize open space and pedestrian safety, including the buffer transition areas between heavy industrial and residential uses.

Through these types of efforts with the community and all its organizations and stakeholders, City Planning respectfully aims to chart a course for a more fair, just, and equitable Los Angeles.